Pedagogical Documentation in Early Childhood

Sharing Children's Learning and Teachers' Thinking

By Susan Stacey, Redleaf Press

Book available on Amazon. Repost from public preview.

https://suestacey.ca/

INTRODUCTION - THE WHY AND THE WHAT

When we notice and value children’s ideas, thinking, questions, and theories about the world and then collect traces of their work (drawings, photographs of the children in action, and transcripts of their words) to share with a wider community, then we are documenting. However, several levels of documentation exist.

The process of documentation becomes pedagogical—a study of the learning taking place—when we try to understand the underlying meaning of the children’s actions and words, describing events in a way that makes our documentation a tool for collaboration, further learning, teacher research, and curriculum development.

Carol Anne Wien provides insight into pedagogical documentation, stating that conceptualizing pedagogical documentation as teacher research calls upon the teacher not to know with certainty but instead to wonder, to inquire with grace into some temporary state of mind and feeling in children. (Wien, Guyevskey, and Berdoussis 2011).

The process of documentation is indeed just that: a process, rather than simply a display. We watch and listen carefully, paying attention not only to children’s play but also to their interactions with each other and with adults and to how they are using materials and their physical environment. In other words, we notice the ways in which the children relate with their world and what they think about that world. They may demonstrate their thinking through words, physical action, art, music, drama, and all the other ways in which children communicate their ideas—their “hundred languages” (Malaguzzi 1993). Therefore, we must be careful observers. We must also be discreet, so we do not interfere with their interactions. If we have been taking notes and photographs, then we have information on which we can reflect.

In a busy classroom, it may be tempting to omit the step of reflection. When we skip this step, it becomes “the missing middle” (Stacey 2009), that is, the all-important pause to reflect that informs our practice. It is difficult to find the time to meet with others in order to reflect together and engage in dialogue. But this is a crucial part of making sense of what children are doing. It helps us decide what we should pay deeper attention to, what we should respond to, and what we should document. In dialogue with our team or our mentors, we share our thoughts, test our theories, and ask each other, “What do you wonder?”

One of the most gratifying results of documenting children’s work is that it supports our growth as teachers in many ways. It demands that we reflect upon our own practices:

When a child has used materials or interacted with others in unexpected ways, when she struggles to bring her ideas to fruition, or when she passionately returns to her project day after day, pedagogical documentation forces us to ask ourselves questions: What is her intent? How can we support her learning? What prior knowledge or experience led to this discovery? What does this mean in terms of what we do tomorrow or next week? If we are to document the child’s thinking or learning respectfully and with insight, we need to reflect on these types of questions.

When we examine our data—photographs, notes, and recordings—we can then engage in intentional practice. Having observed, recorded, and reflected, we can make carefully crafted decisions about how to respond to the child. Perhaps we have a vast quantity of information and must carefully consider what, exactly, is important to respond to—and when—for we cannot respond to everything we see.

When we tease out what we consider to be important for a child and put this together into a documentation panel or page, the process often leads us to next steps. In this way, curriculum becomes a collaboration between children and educators. And when we share pedagogical documentation with children, giving them an opportunity for further response, we become co-owners of the curriculum. How the children respond—what they say, what they notice, how they engage with the documentation—will inform our decisions about what to do next.

Ann Pelo, Margie Carter, and Deb Curtis describe this type of thinking and responding in Carter and Curtis’s (2010) book, The Visionary Director, calling it “A Thinking Lens for Reflection and Inquiry®”:

- Knowing Yourself

- Examining the Physical/Social/Emotional Environment

- Seeking the Child’s Point of View

- Finding the Details that Engage Your Heart and Mind

- Expanding Perspectives through Collaboration and Research

- Considering Opportunities and Possibilities for Next Steps

These six points remind us to pay attention to our emotional responses to each moment with children, to keep our values in mind, to think about the children’s thinking, to collaborate with others, and to reflect before we take action. When we think about the cycle of inquiry—observing, reflecting, documenting, sharing, and responding—we can see that pedagogical documentation has the capacity to inform our classroom life in profound ways. It can influence children’s and teachers’ learning together and contribute to the development of a truly responsive curriculum. Documentation becomes so much more than display.

Bio: Susan Stacey is an early childhood consultant and teacher educator with more than thirty years of experience in the field. Much of her time has been in lab schools, where she worked with children, educated teachers and student teachers, conducted research, and developed curriculum. Other roles include work as a preschool teacher, director, and college-level instruction. She presents widely on emergent curriculum, observation, and documentation.

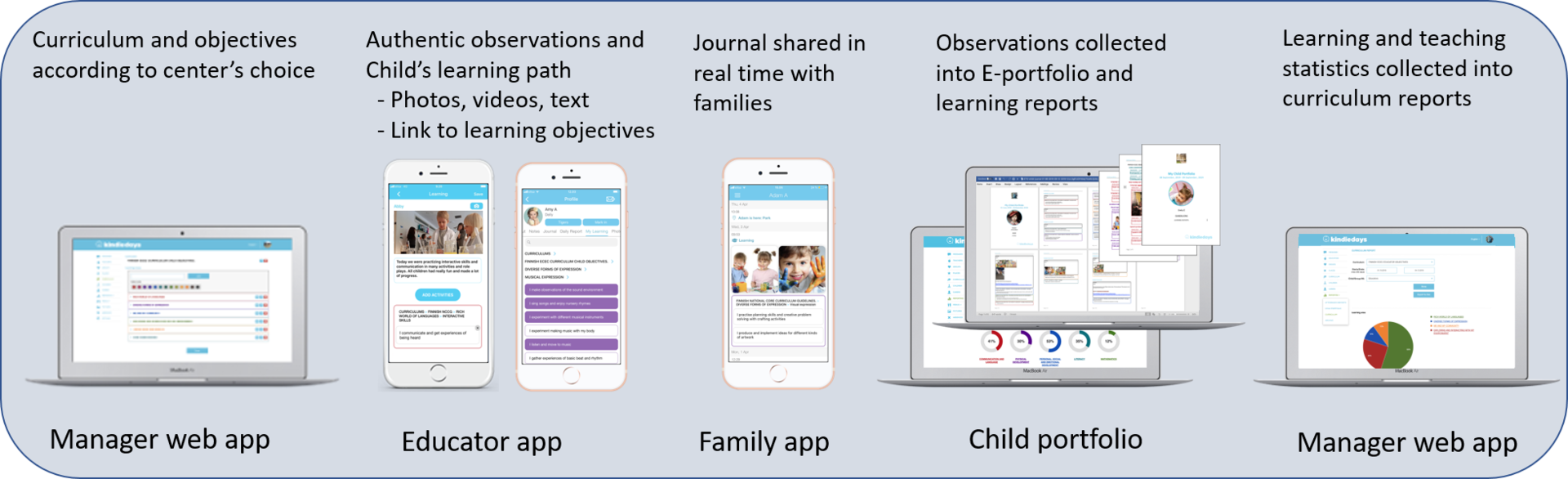

Pedagogical Documentation is one of the cornerstones of Finnish Early Childhood Education. Of all the obstacles that educators face trying to to document children's work, simply finding the time and right working methods is perhaps most challenging. Contact us to learn how Kindiedays can take your center to a new level by saving time from tedious non-teaching activities and providing support for children's education. With Kindiedays Pedagogical Documentation solution you smoothly and efficiently track the children's learning progress and guarantee that every child gets to reach their personal best.

HOW TO GET STARTED WITH PEDAGOGICAL DOCUMENTATION?

Pedagogical Documentation is one of the cornerstones of Finnish Early Childhood Education. But of all the obstacles that educators face trying to to document children's work, simply finding the time and right working methods is perhaps most challenging. Just using manual working methods and tools is too cumbersome and leaves too little time to provide quality education.

Overall you will need to rethink your work with the children. With smart working methods and an efficient digital solution, such as Kindiedays, you will have time for the children and also do Pedagogical Documentation to reach the goals above. In the Post section on our web page we have collected a lot of useful guidance for you to explore.

Contact us to learn how Kindiedays can take your center to a new level by saving time from tedious non-teaching activities and providing support for children's education. With Kindiedays Pedagogical Documentation solution you smoothly and efficiently track the children's learning progress and guarantee that every child gets to reach their personal best.